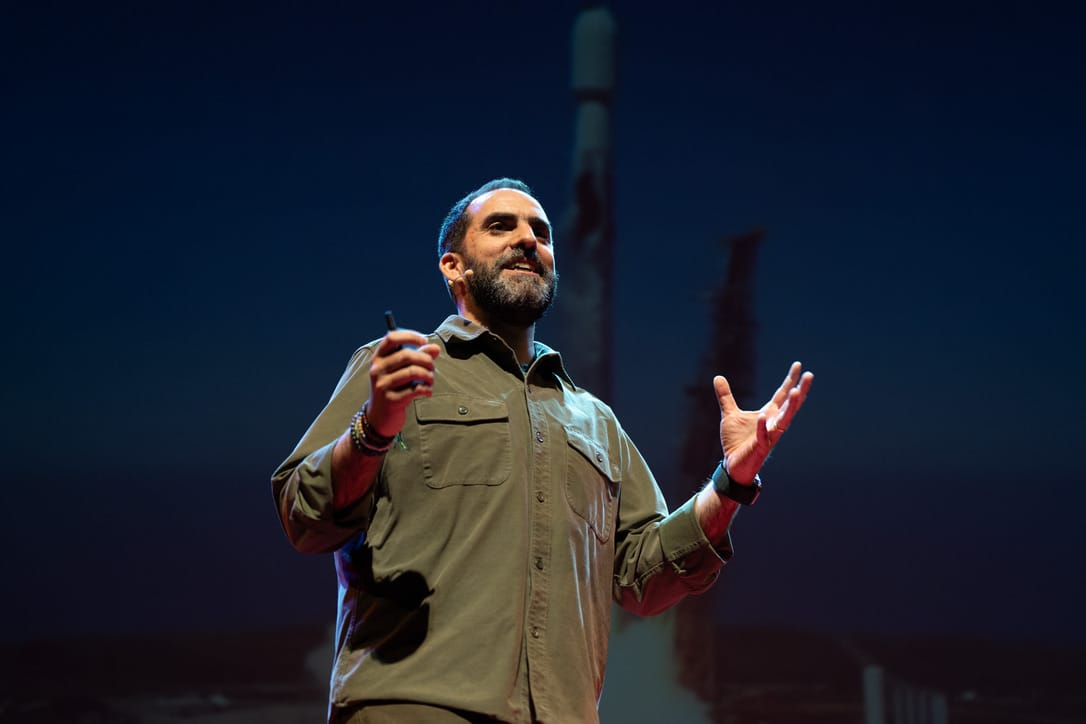

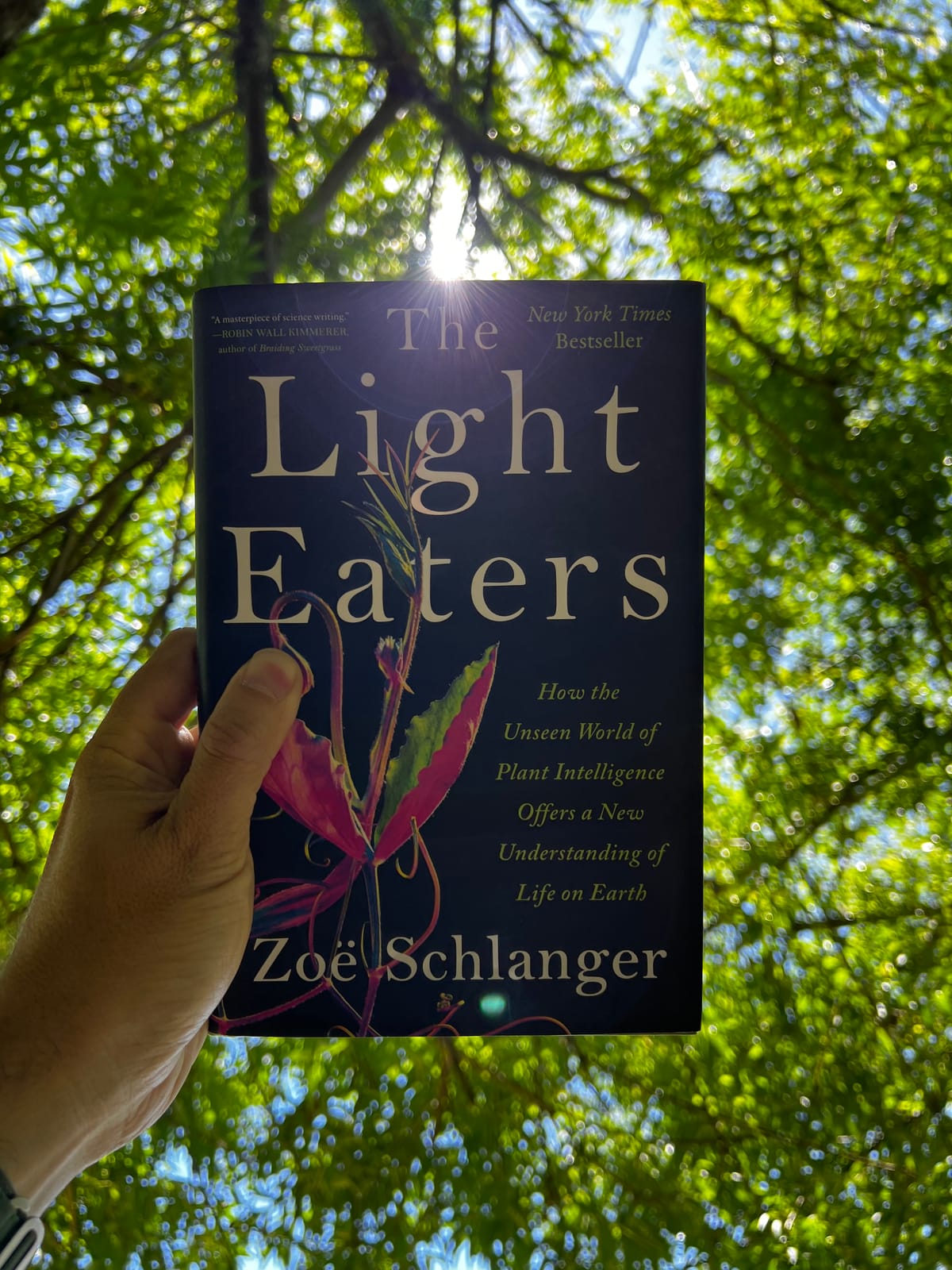

The Light Eaters (2024)

Plants may be the most effective collective intelligence Earth has ever evolved—distributed, adaptive, and networked by nature.

I didn’t plan to read this book. But I’m so glad I did—my favorite book of 2024.

I’ve been avoiding new releases, purposefully leaning into early editions of the classics—Humboldt, Darwin, Asimov, Sagan, Hawking. But after finishing The Invention of Nature (2015), Amazon recommended this strange, glowing title. And I’ll admit: I picked it by its cover. It just looked... delicious.

I’m glad I trusted that instinct.

This isn’t just a book about plants. It’s about intelligence, perception, and responsiveness—emerging in silence, and until recently, with very little recognition.

Schlanger opens with her own climate fatigue—a personal reckoning that, for some, may feel distant or privileged. But what follows is a shift; from disillusionment to awe. As she dives deeper into the science, her reporting becomes more rigorous and expansive. She balances evidence with distance, never losing her voice.

The wood-wide web was just the beginning.

Beyond Metaphor

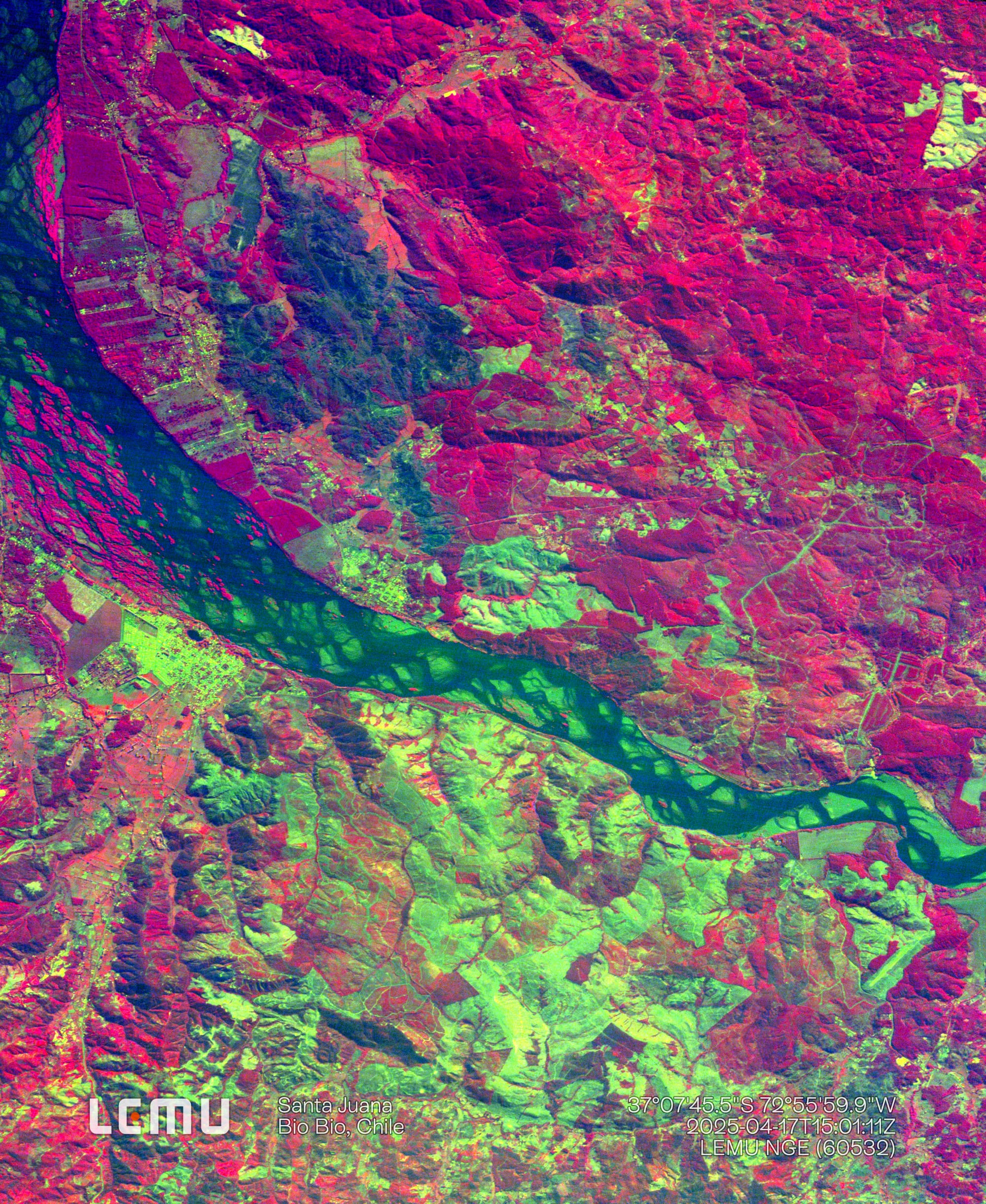

One of the most striking chapters explores Boquila trifoliolata—known around here as Pilpilvoqui or Voqui Blanco—a “chameleon vine” from Chile’s Valdivian rainforest that mimics the leaves of the species it climbs. Shape, size, color, orientation. Even artificial plants.

The mechanism remains unknown—an open question hiding in plain sight, in one of the most studied ecosystems on the continent.

And yet, despite being known to locals for generations, it only entered scientific literature in the last decade (Gianoli, 2014). A reminder that even in the first quarter of the 21st century, many of nature’s most extraordinary behaviors remain undocumented—not because they aren’t valuable, but because our attention tends to orbit what’s trending, not what’s quietly complex.

Schlanger doesn’t moralize that gap. She reveals it—and invites us to look again.

Beyond Comprehension

This isn’t about whether plants are “like us.” It’s about the limits of our imagination.

Because what The Light Eaters makes clear is that plant intelligence is not like human thinking. It’s something entirely different—and far older. Quiet, efficient, and collective. Evolving for hundreds of millions of years in every forest, field, and kelp bed.

This book reminds us that intelligence is not something we understand, yet.