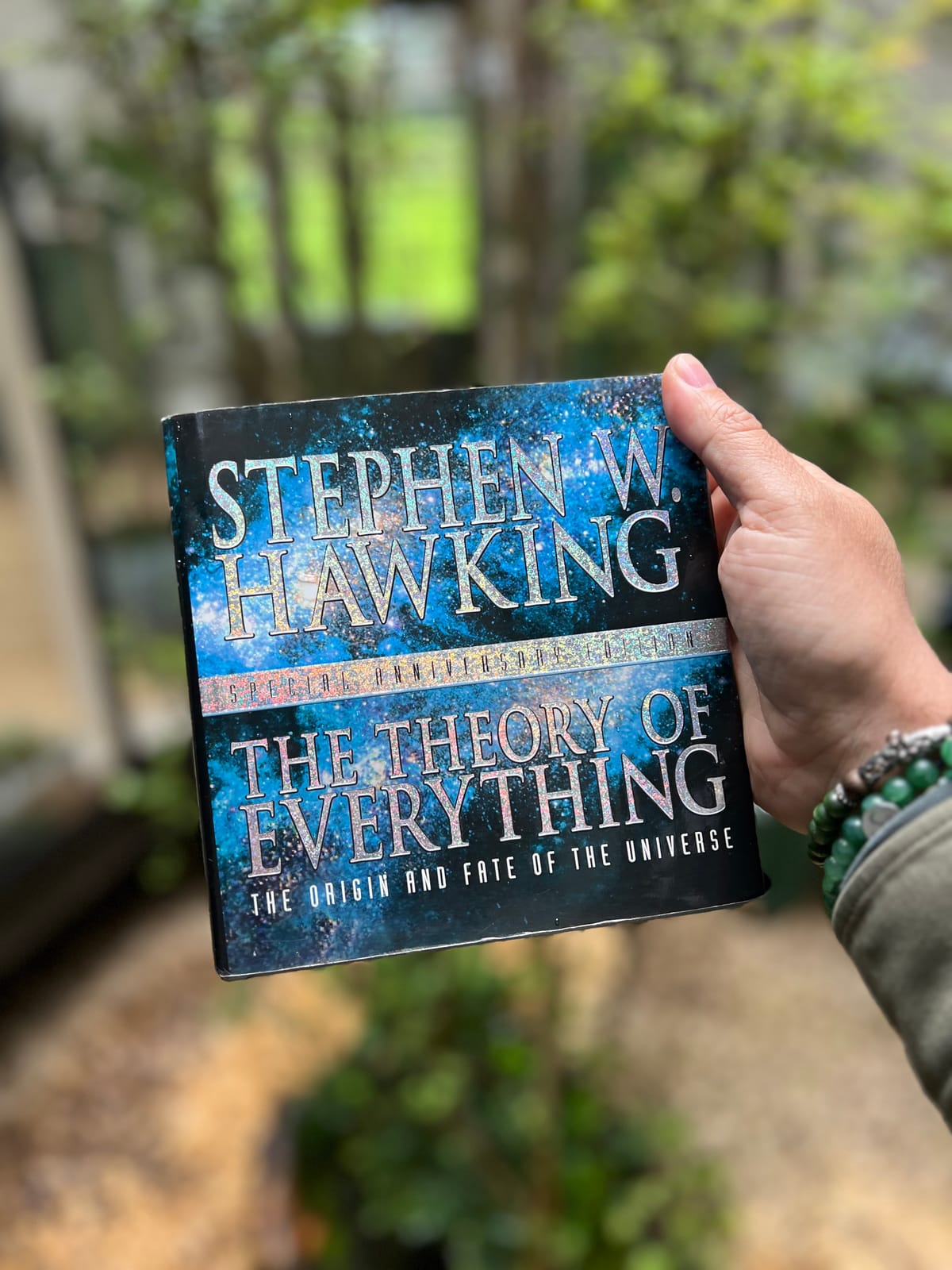

The Theory of Everything (2002)

Why the ultimate theory must be simple.

“If we do discover a complete theory, it should in time be understandable in broad principle by everyone, not just a few scientists.”

— Stephen Hawking

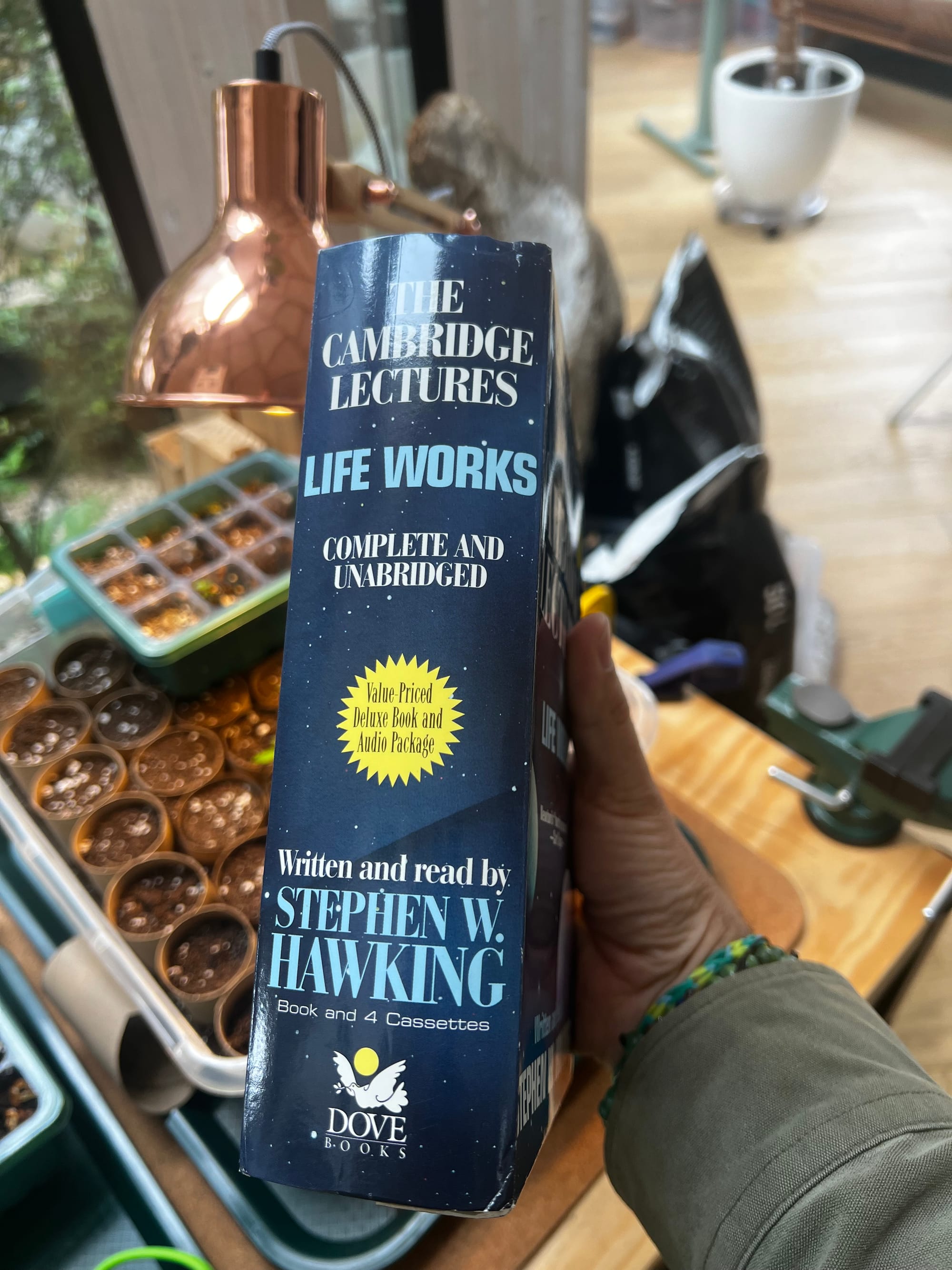

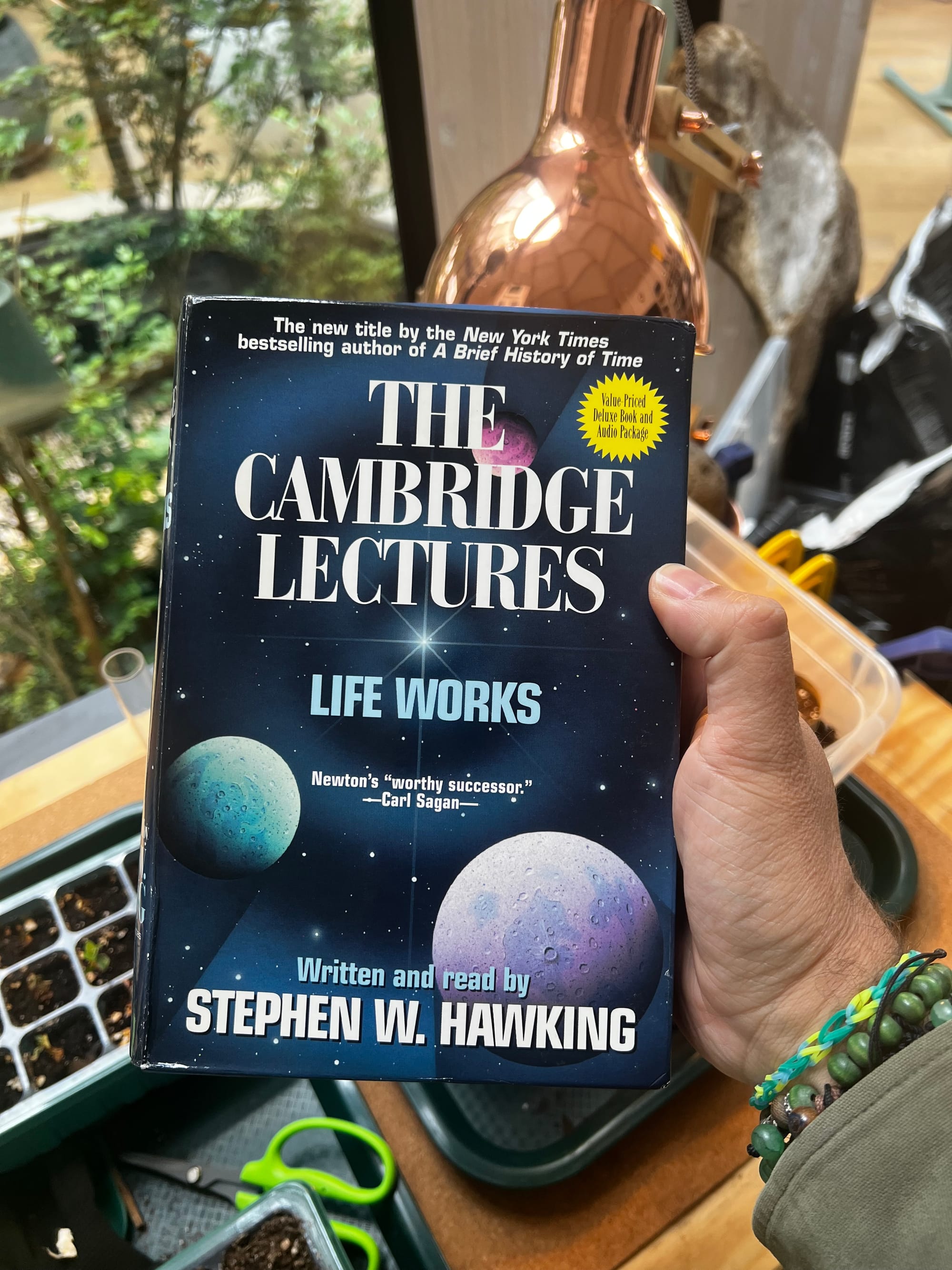

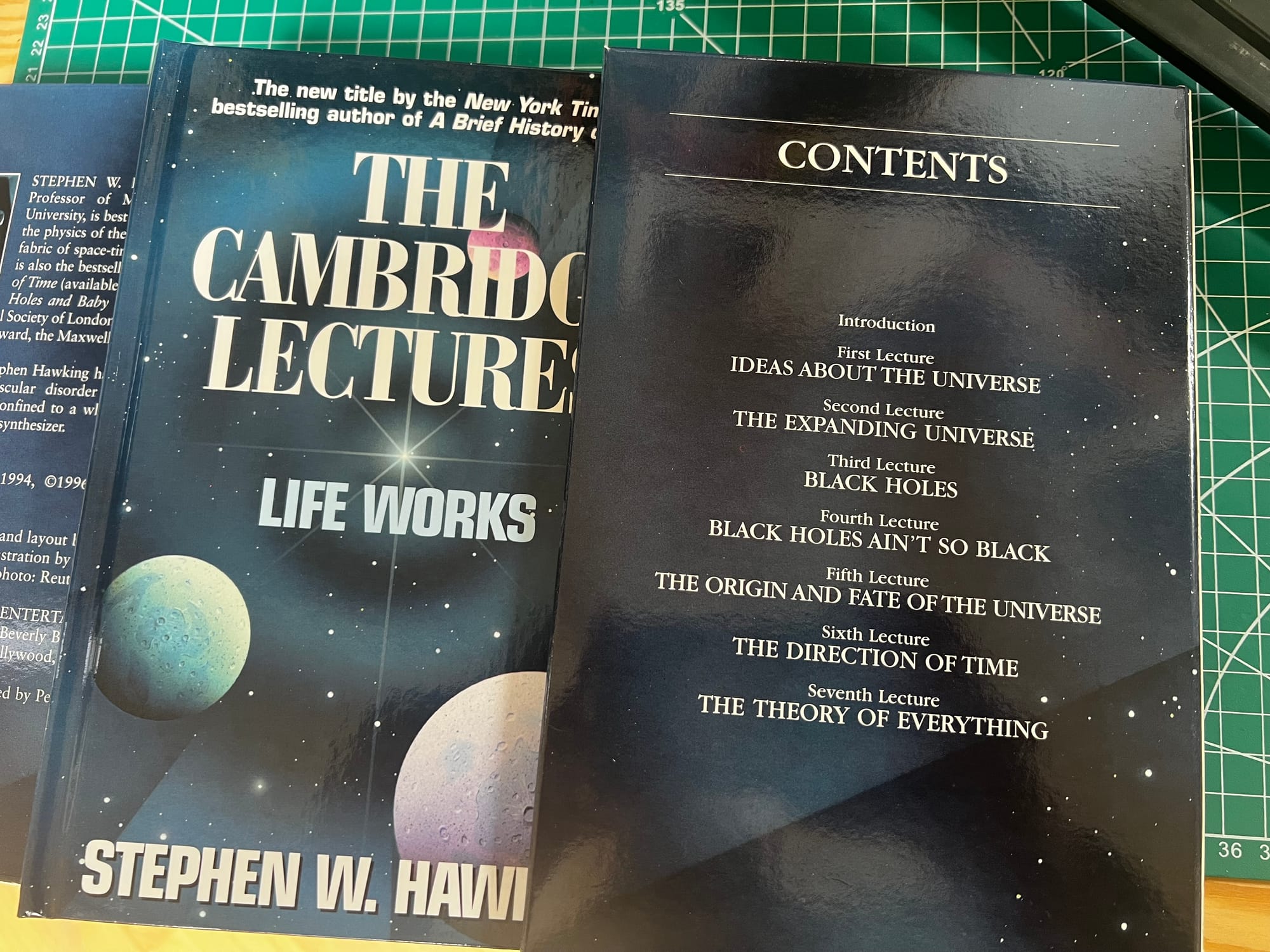

Stephen Hawking’s 💿 The Theory of Everything gathers lectures he gave at Cambridge in 1996, later compiled as The Cambridge Lectures: Life Works and republished in 2002 under this new title. But the way to experience it is not on text — it’s through his voice.

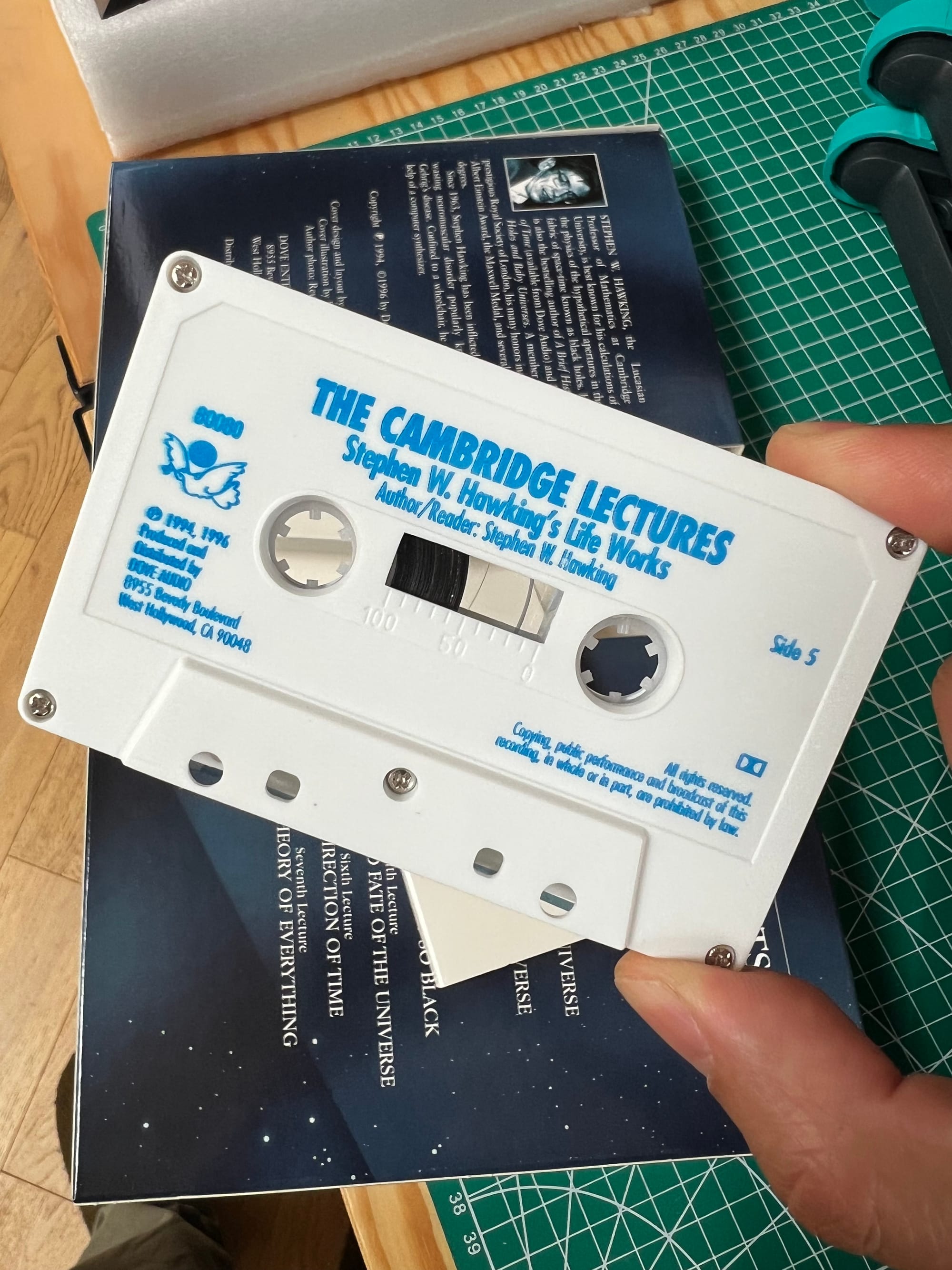

Still can't believe I got the original lectures from 1996 — in cassette! — in perfect condition from a thrift store.

Not his natural voice, but the synthesized one generated by a 1980s DECtalk machine — a device long obsolete by 2002, but inseparable from him.

At first it sounds mechanical, awkward even. And then, almost immediately, you forget the machine. What remains is Hawking’s mind: his clarity, his wit, his ability to make the universe feel close. Even when reciting unfathomable numbers.

He takes us on a journey through the history of astronomy. From Aristotle and Ptolemy, to Newton, to Einstein, to quantum mechanics. Centuries of human attempts to locate ourselves in time and space. Always provisional, always expanding.

Hawking’s humor slips in unexpectedly, puncturing the heaviness of the cosmos.

A reminder of the power of the written word: even when synthesized by a primitive machine, it can hold so much character you glimpse the person behind it.

The most important lesson I carried with me: if there ever is a “theory of everything,” it will have to be simple. Like every theory that changed our understanding of the world.

Elegance is not a constraint, it’s a necessity.

And that’s the paradox: simplicity that describes the vastest scales of time and space. Complexity distilled into something a child can grasp, even if our brains still struggle to hold its immensity.

Meaningful things must be simple. That doesn’t make them easy.

A reminder, once more, of our need to measure centuries, not seconds.