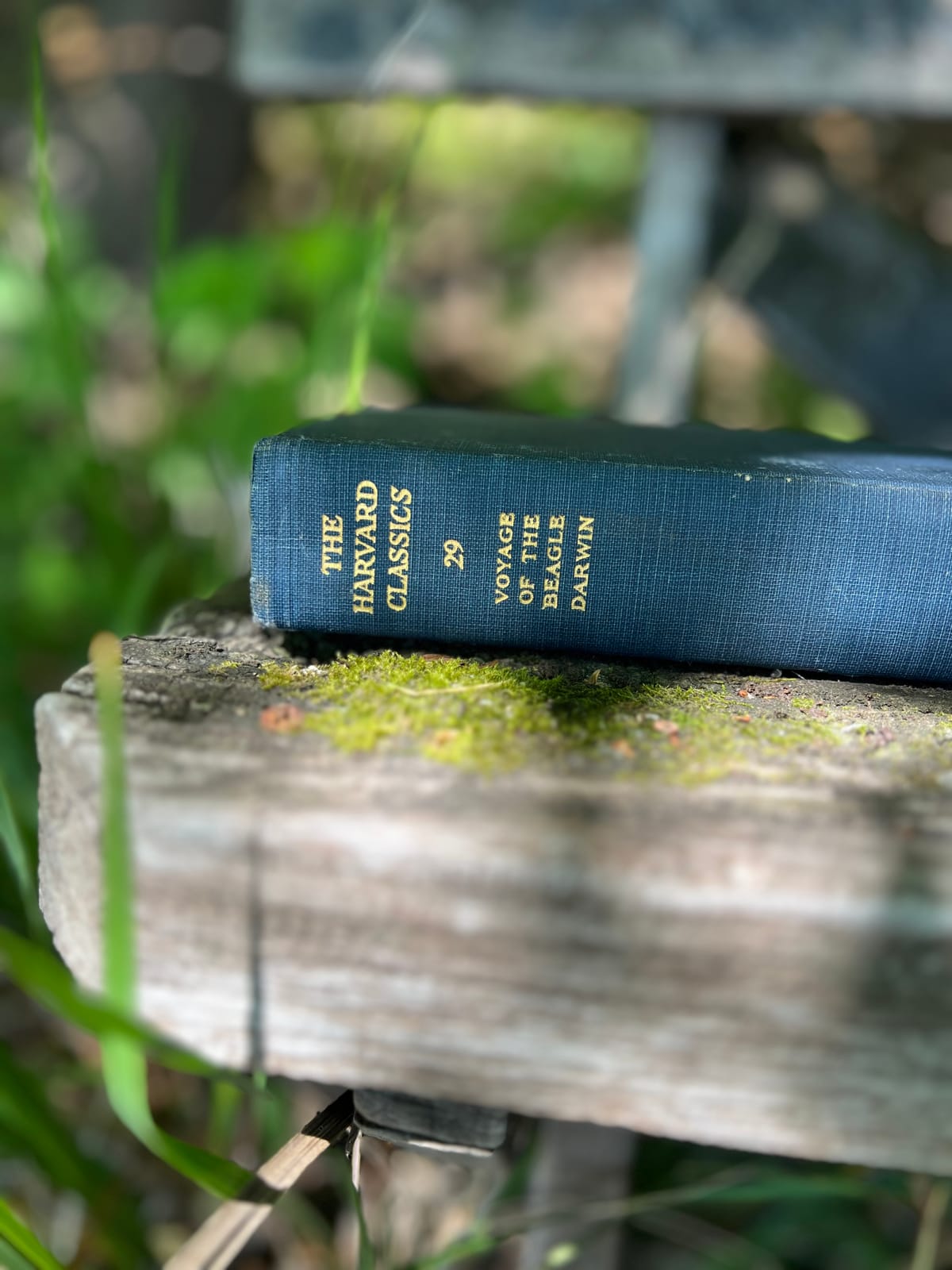

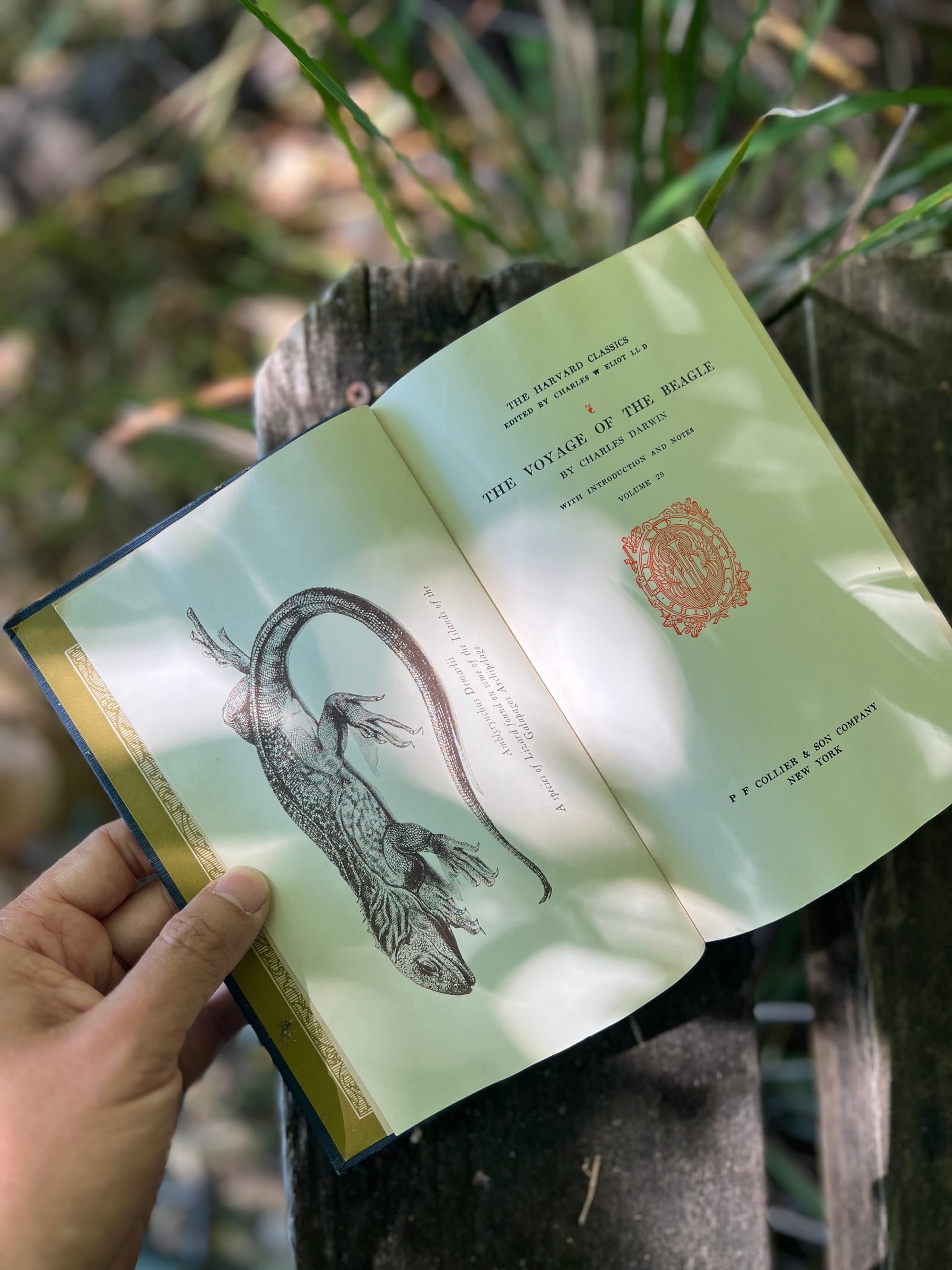

The Voyage of the Beagle (1839)

This field journal is a time capsule.

Reading this 1909 edition felt one step closer to stepping aboard the HMS Beagle myself—guided by a young Darwin, just 22 years old, on a five-year journey that would eventually shape modern science.

His writing is startlingly vivid: You can smell the air in Patagonia, feel the damp heat of Brazil, sense the chill in Valdivia. Much like Humboldt before him, Darwin doesn’t just describe landscapes—he captures atmospheres.

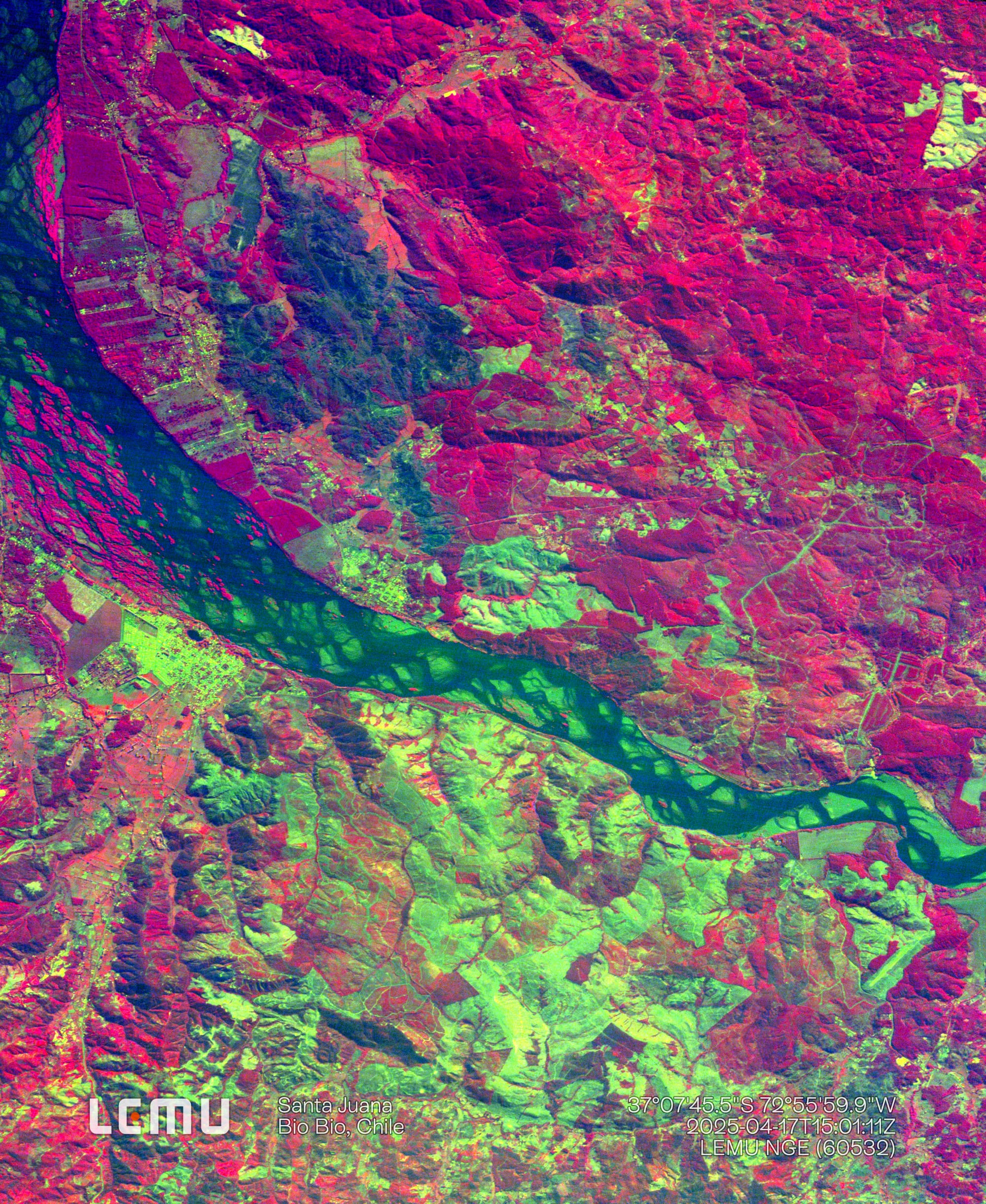

What made this book unforgettable for me was how often Darwin passed through the very ecosystems I’ve come to know very well: Chiloé, Valdivia, the kelp forests off the Southern Pacific.

His description of a volcanic eruption seen from Chiloé, his trek across the Andes from Limache to Argentina, and his impressions of Valparaíso feel like time-travel postcards.

Reading those chapters was especially fascinating—seeing these very places through the eyes of someone writing almost two centuries ago.

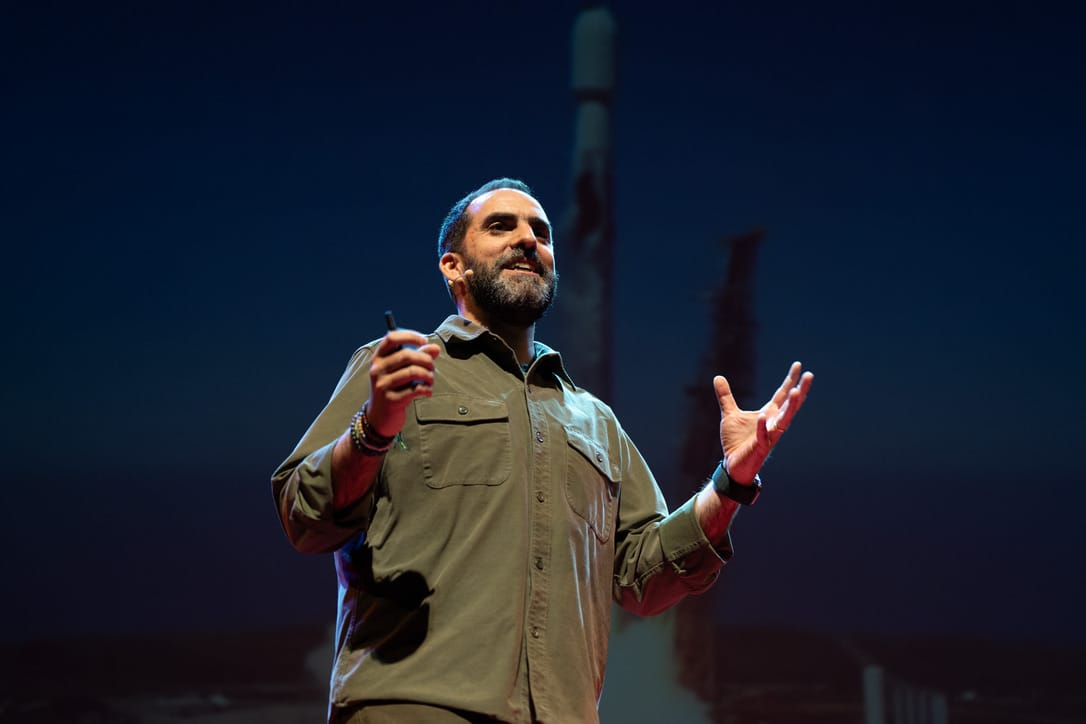

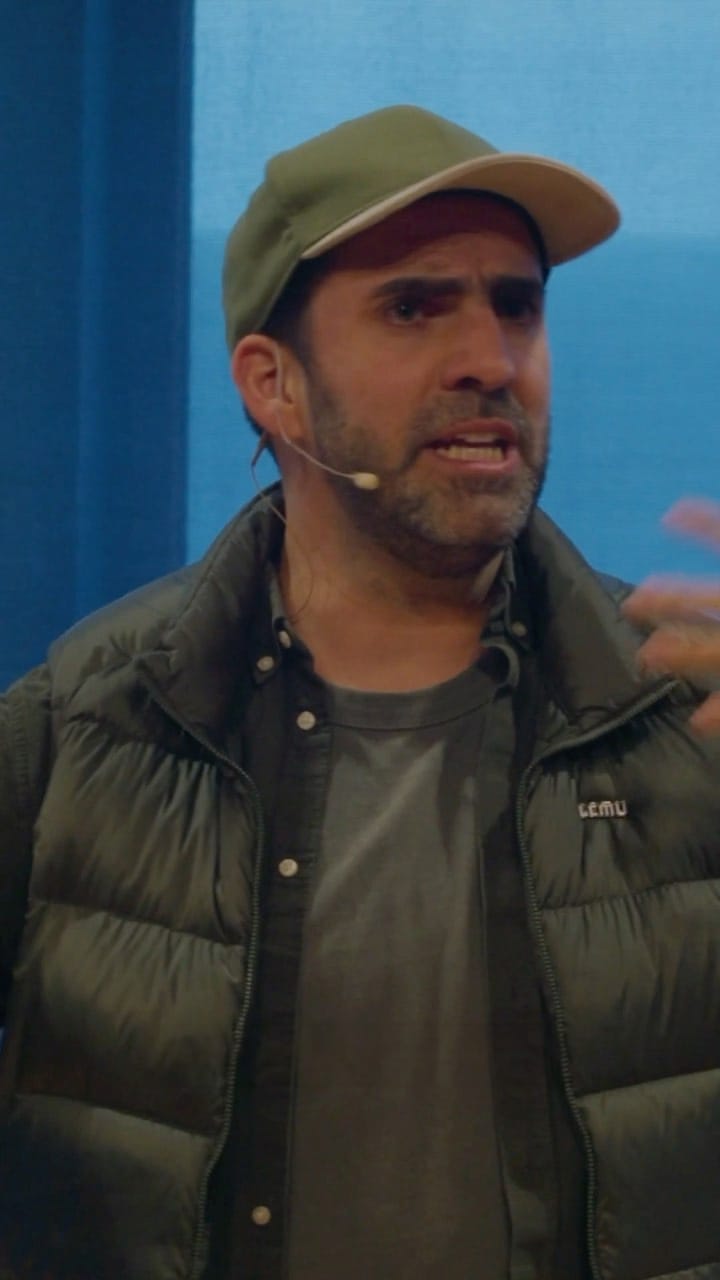

A Young Mind in an Increasingly Complex World

Darwin’s observations are often brilliant—but just as often shaped by the worldview of a young British traveler in the 1830s.

He casually divides people into “civilized” or “savage,” praises Chileans for their “commercial character,” and describes the indigenous people of the Pampas or Tierra del Fuego through a colonial gaze.

These are not scientific conclusions—they’re reflections from a cultural context he hadn’t yet learned to question.

And that’s part of what makes The Voyage of the Beagle so human. It’s not the voice of an authority—it’s the voice of someone learning, questioning, slowly expanding his lens (and thoroughly quoting his influences).

That shift becomes especially clear once he reaches the Galápagos, where you feel the early weight of what would become evolutionary theory. The observations become more layered. The questions more open-ended.

Extinction Foretold

One of the most haunting moments is his description of the Falkland Islands wolf. Darwin notes how unafraid it is of humans, and predicts—accurately—that it will soon vanish.

It was hunted to extinction just decades later.

That passage hits hard. He didn’t mourn the loss—but he recognized it as inevitable, simply because the species had no fear of humans.

And that insight recurs again and again: Animals disappearing not due to ecological collapse, but because they were too trusting.

The Voyage of the Beagle becomes a record of a planet losing its biodiversity just as it was being documented. A snapshot of life that would soon be gone.

A World Already Changing

That’s what makes The Voyage of the Beagle so much more than a scientific origin story. It’s a chronicle of disappearance in real time.

We’ve refined our tools and softened our language, but the deeper logic remains: We still treat the living world as if it were limitless—mistaking abundance for permanence.

Darwin didn’t know what his journey would become.

He wasn’t trying to make history—he was just paying attention.

But what he saw, what he wrote, still asks something of us today:

What are we doing with the knowledge we have today?

This book is a glimpse into a young, curious mind encountering the world in all its complexity—beauty, brutality, and change.

But reading it now, nearly two centuries later, it’s impossible not to realize how much of that world has vanished.

Despite all the knowledge we generate each day, we still understand so little of nature—or how much of it has already slipped away.

PS: You can tell by the pictures how much I enjoyed reading this wonderful piece of history, by the Panguipulli lake, this summer.