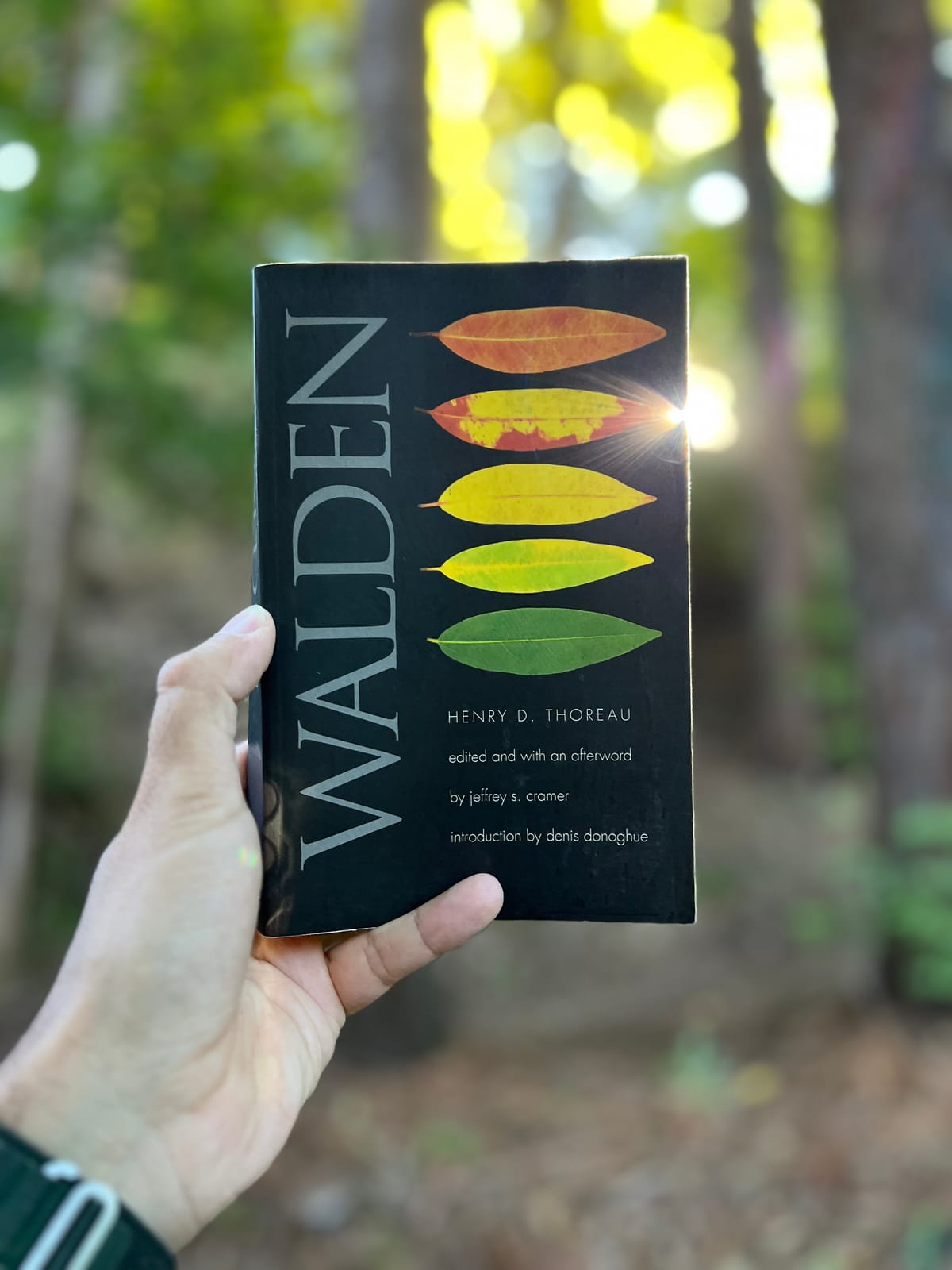

Walden (1854)

Long before smartphones or social networks, Thoreau had already seen the crisis coming.

I understand this book is part of many high school reading lists in the U.S. (and if it isn’t in all of them, it should be). It found me in my mid-40s—and I’m so glad it did.

What stayed with me wasn’t just the solitude, or the stillness. It was Thoreau’s deep unease with speed.

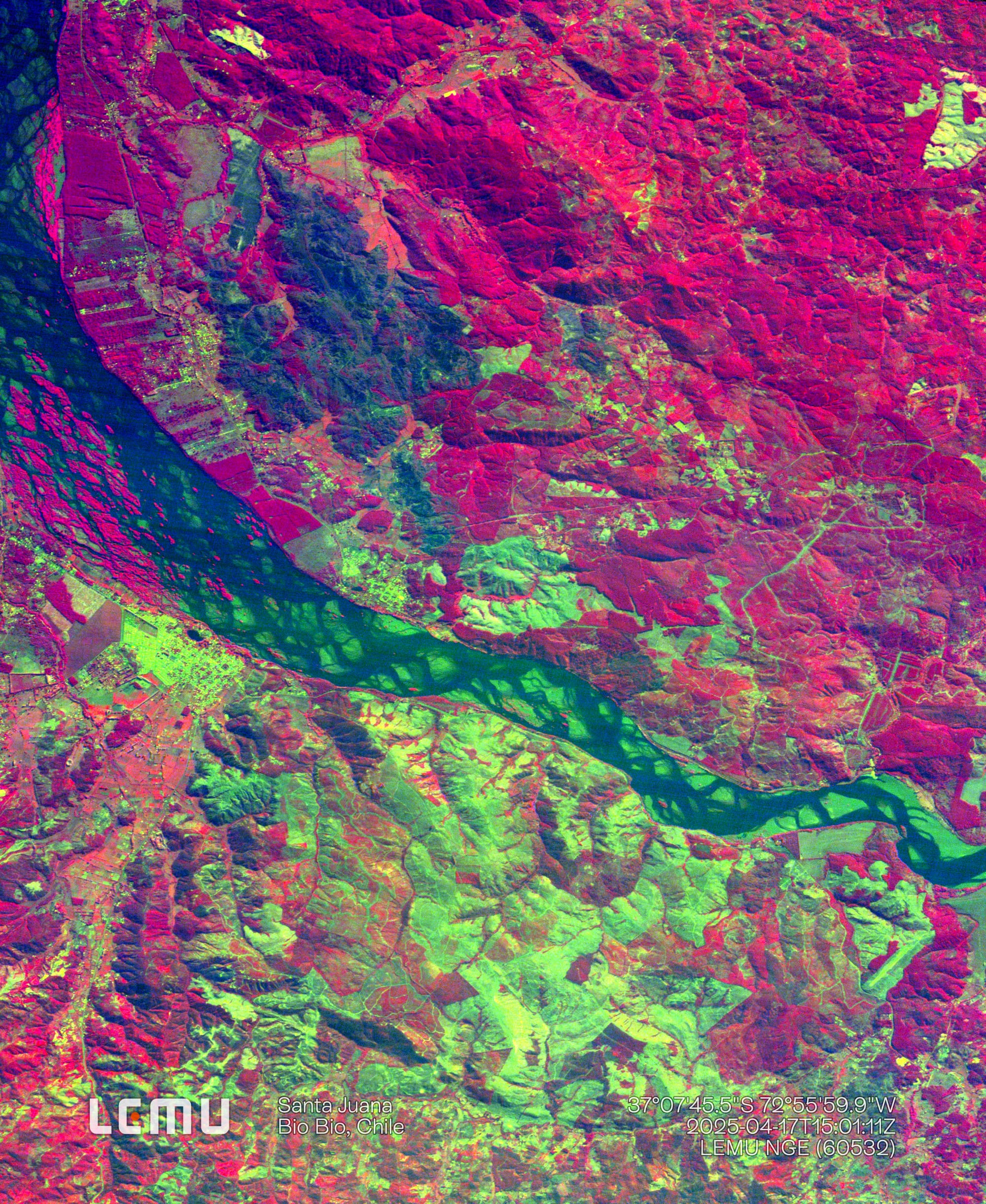

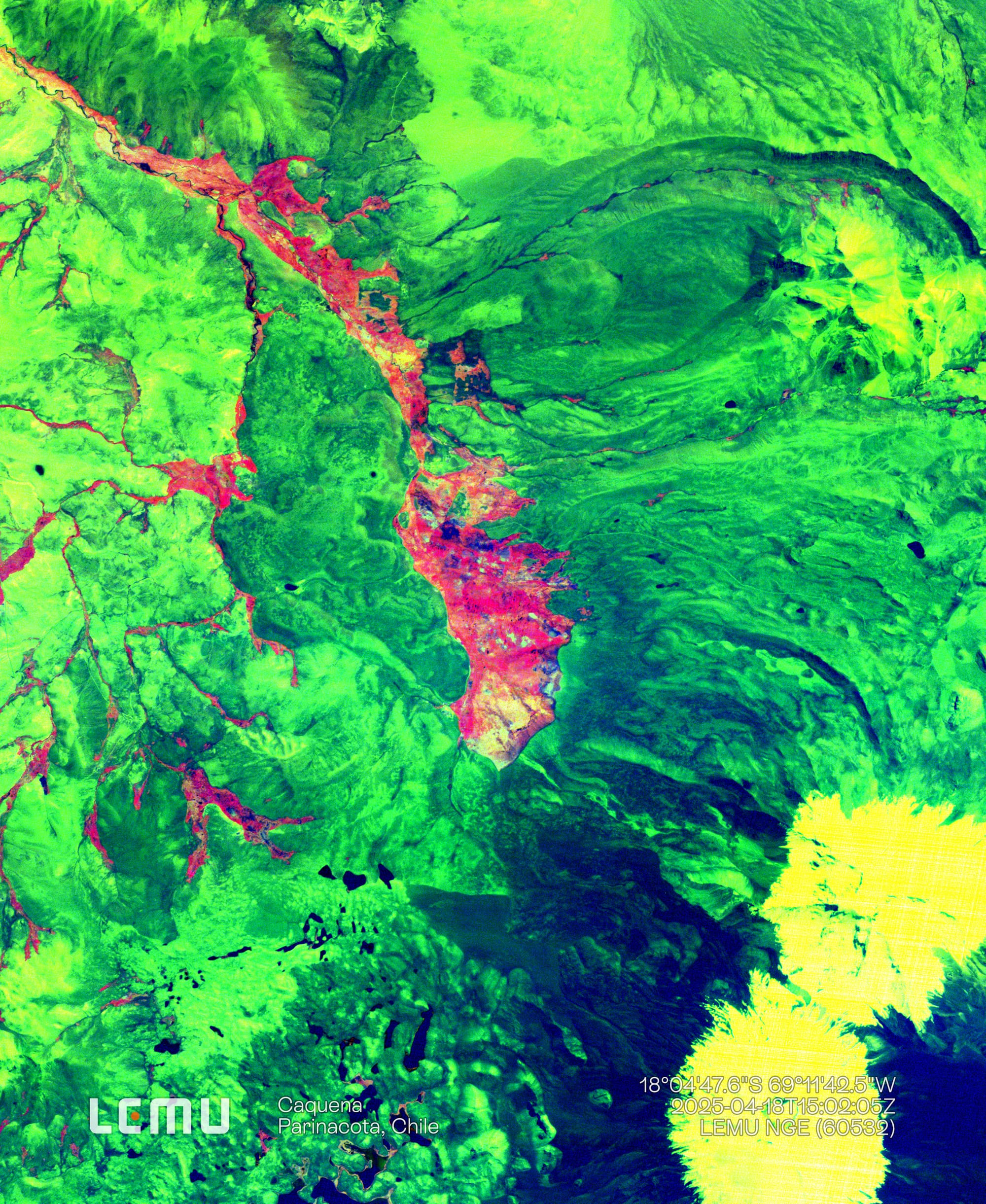

The sense that society, even 185 years ago, was already accelerating past its capacity to stay connected with the natural world.

Walden is a book-length reminder that we’re not just moving fast—we’re moving without asking where we’re going.

Even the slower parts—yes, even the long passages where he counts his beans and logs his expenses—felt strangely valuable. Because maybe that’s part of the lesson too: That paying close attention to the mundane is how we begin to slow down. And slowing down is how we start to see again.

Thoreau didn’t retreat to the woods to escape the world. He went to understand it better—to measure life by something other than urgency.

Walden helps us remember that we don’t achieve more by moving faster.

We achieve more by focusing on our compass, not our watch.

Thoreau doesn’t preach minimalism; he questions excess. He doesn’t romanticize nature; he simply pays attention to it.

There’s a moment where he describes, in excruciating detail, a violent battle between red and black ants on the wood chips by his cabin. He crouches down, even picks up a chip to observe them more closely under glass. It seems excessively nuanced—until you realize he’s describing with the same thoroughness we’d reserve for a human war.

That kind of presence is rare now. And reading him today feels quietly radical. Because stillness—real stillness—is a kind of resistance. Not against technology, but against forgetting what came before it. Against speed without direction.

Thoreau wasn’t trying to disappear (he wouldn’t’ve published a book if he was).

He was trying to see clearly. To ask what we’re living for, and whether the way we live reflects that answer. These questions haven’t aged. If anything, they’ve deepened in relevance.

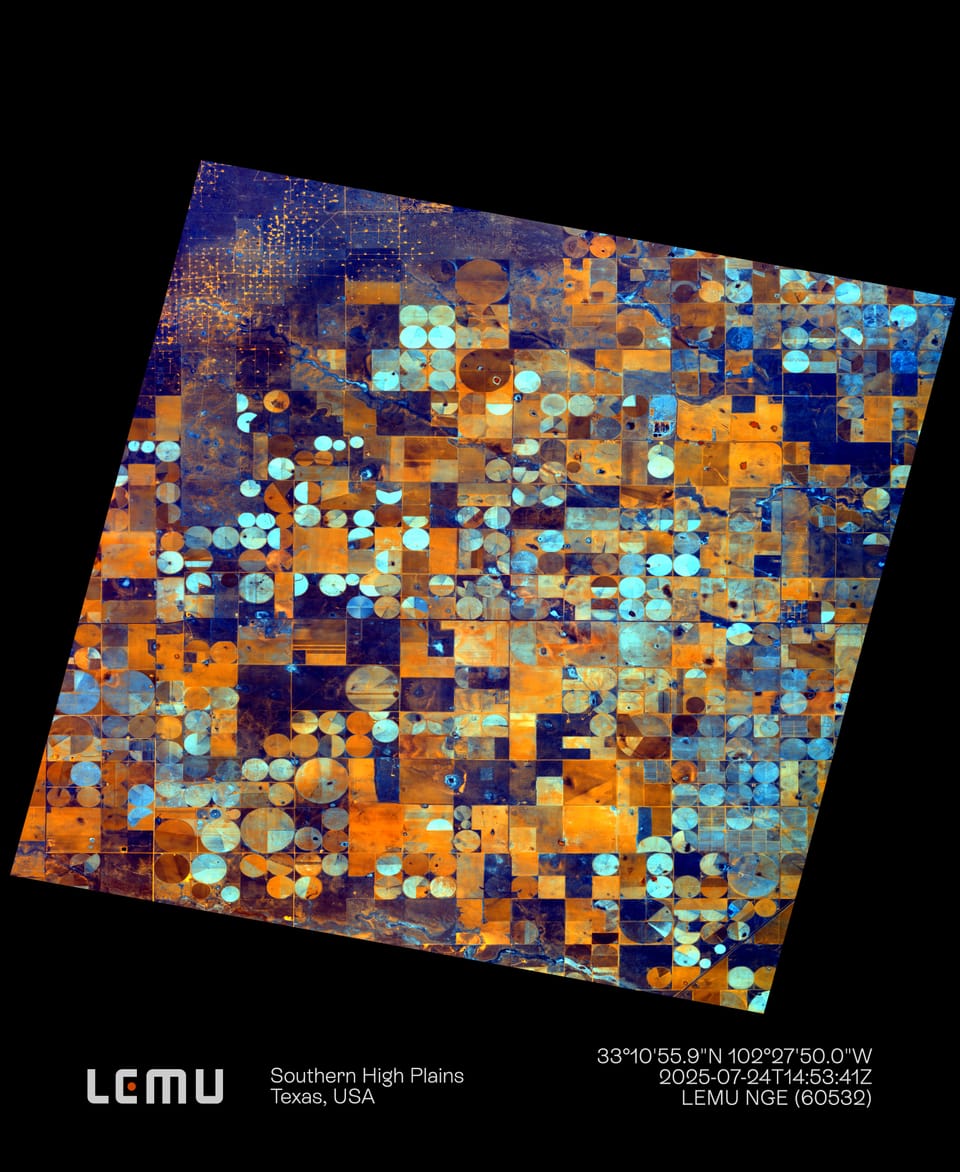

We’ve built faster machines, smarter tools, and louder networks. But Walden reminds us that the real challenge isn’t technical—it’s human.

It's about how we live, what we notice, and what kind of relationship we want with the rest of our natural world.

This book may be almost two centuries old, but it reads like a letter to the present.

A quiet, persistent reminder that slowing down isn’t failure—it’s wisdom.

And that the future we want won’t come from outrunning the crisis, but from reconnecting with what we left behind.